Women Lead the Rescue

Riverside, Ill. March 24, 1917. The Fuller Sisters, three Portsmouth-born women who traveled around the world singing traditional folk songs, sat in the living room of the Scottish Home. The residents of the red-bricked two-story home listened as the talented women played the harp and sang. Folk songs such as Moving the Barley and I’m Seventeen Come Sunday were a joyful addition to the already relaxed environment of the evening. Cora J. Cummings, the superintendent of the home, wrote the following in her nightly records:

“[The Fuller Sisters] came out to divert the old people, and people were enthusiastic in their applause and praise, and, as the sisters kindly responded to their pressing appeals for encores, were kept up later than usual.”

-Cora J. Cummings, March 24, 1917.

The sisters (from left, Cynthia (Oriska) playing the harp, Dorothy and Rosalind), on a Midwestern tour arranged by their father.

As the early, cold spring winds tore through the trees in the woods beyond the property, a small electrical fire began in the basement boiler room. Topsy and McDougal, the home’s resident dogs, sounded the alarm. They found their way into Cora’s room and there by her bedside barked and howled until Cora woke. When she did, she found her own bedroom full of smoke. Holding her breath and keeping crouched low to the ground, she managed to get to the hallway to ring the alarm bell. This awakened the residents and the chief nurse Ms. Lula Peterson. The two women then began the arduous task of getting each and every resident outside to safety.

Those on the first floor simply walked out of the front door, albeit in their night clothes, into the frigid air. The stairwell was on fire, and those residents on the second floor fled up a fire escape and onto the roof to await rescue. Help was coming from Riverside, Cicero, and Berwyn, but the fire departments were over two miles away. When help finally arrived, the firefighters quickly rescued the residents on the roof. But due to lack of water, dry air, and fierce winds, they were unable to extinguish the raging fire. All anyone could do was watch as flames reduced the original building to rubble and ash.

The building, valued at 40,000 dollars, was destroyed. The residents lost everything they owned. Of the thirty-seven residents, only four were casualties that night–residents who had gone back into the burning building to retrieve valuable items. And though Topsy the Collie emerged from the ruins unscathed, little McDougal, his terrier friend, was lost. He died a hero, though, responsible for preventing even greater tragedy.

The Aftermath

Within hours of the fire, donations started pouring in at the Riverside Town Hall. As word spread, concerned and curious citizens arrived at the still-smoldering scene to find that only a few walls remained standing. Smoke and char hung thick in the air, blanketing the village of Riverside. John Williamson, of 1441 Washington Boulevard in Chicago, was the first to arrive. He, along with fellow Illinois Saint Andrew’s Society members James B. Forgan, John G. Keith, Daniel Ross Cameron, Thomas Innes, Daniel Campbell, Alexander Robertson, Hugh Richie, Robert Falconer, W.B. Mundie, the Reverend James MacLagan, James Glass, and John Crerar, surveyed the scene. They talked of the ruins, of the loss of life, but more importantly, the future of the home. As they stood in the still warm embers, Williamson declared that “the Scottish Home must not die in its own ashes!”

Ms. Dorothea Somerville, head of the local charity organization, took charge of caring for the survivors. Because the home was a total loss, the residents (inmates as they were called back then) needed temporary housing. There was some room at the hospital, but most of the home’s residents took private shelter, staying with relatives and neighbors who offered free room and board. Those that had no other option were housed in rented quarters.

Because the residents were left with nothing but their pajamas, the charitable people of Riverside collected and donated clothing, furniture, food, and other items. Word traveled back across the pond, and the Western British American newspaper wrote that “[No resident of Riverside who helped] was Scottish; but each was a rare example of the rarest of blessings – the friend in need.” The villagers were a shoulder to lean on, and the residents were lucky to have their own well-being looked after so lovingly.

Rebuilding Overnight

As word of the devastation spread, Scots from around the country gave what they could. A Mr.William Scott of New York City gave a donation of $3,000 while fellow New Yorker William B. Walker offered $500. Even non-Scots were touched by the tragedy. E.G. Elcock enclosed a check for $1,000. Williamson, McGill, and Forgan themselves also contributed $1,000 each. The current Illinois Saint Andrews Society president Joseph Cormack gave $500, as did treasurer Alexander Robertson and another Society member Charles M. MacFarlane. A few days after the fire, John Williamson called an emergency meeting of the Board of Governors. His office was located in the recently constructed People’s Gas Building, which still stands at the corner of Adams Street and Michigan Avenue in Chicago, IL. It was there they decided that the Scottish home would be rebuilt. But the war was imminent, and other investors–namely those who had helped with the initial funding and construction of the building, were hesitant. The cost would be double the original, and while there had been a coordinated effort in 1910 to establish a Scottish institution for the aged, participating parties were no longer interested, instead focusing their concerns on American-German relations. Despite the difficulties, they were able to raise $5,150.00 virtually overnight, all of which would go towards taking care of the homeless residents as they awaited the construction of the new home.

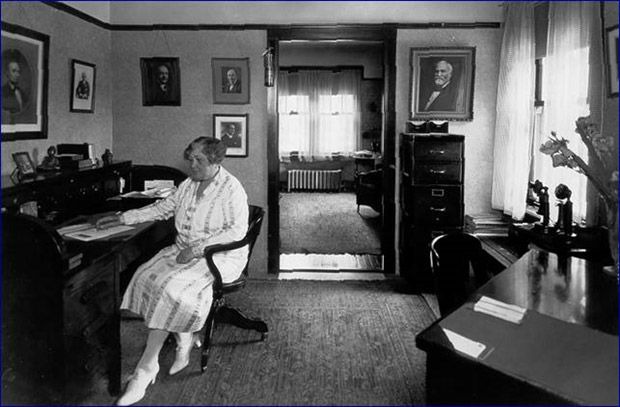

William Bryce Mundie

The People’s Gas Building today.

The members of the Saint Andrew’s Society had to raise the funds for the new structure on their own. Alexander Robertson, the Vice President of the Continental and Commercial National Bank, was named treasurer and began seeking contributions from American and Scottish people of Chicago. The expected cost to rebuild was estimated at 100,000.00 (approximately 1.67 million dollars today). Miraculously, Robertson raised the money in just two short weeks! The chief architect of both the original and newly planned structure, William Bryce Mundie was also at this meeting. He promised to design a new Scottish Home that looked just like the original but this time would be designed so that a tragedy like this one never happened again. With America’s involvement in WWI on the horizon, the work had to commence immediately. And it did; within six months the new building was completed and stands in the same spot today.

Every year at our Scottish Festival & Highland Games, the Chicago Scots feature a family or an organization as our Honored Clan. This year, to recognize and celebrate its’ strong Scottish roots, our Honored Clan is Rotary International. We are proud to announce that Rotary International’s Scottish President, Gordon McInally has agreed to lead our Parade of Tartans at 12:30 p.m. Gordon will also receive the Salute to the Chieftain from the Massed Pipe Bands at approximately 6.30pm on Saturday, June 15, 2024.

Every year at our Scottish Festival & Highland Games, the Chicago Scots feature a family or an organization as our Honored Clan. This year, to recognize and celebrate its’ strong Scottish roots, our Honored Clan is Rotary International. We are proud to announce that Rotary International’s Scottish President, Gordon McInally has agreed to lead our Parade of Tartans at 12:30 p.m. Gordon will also receive the Salute to the Chieftain from the Massed Pipe Bands at approximately 6.30pm on Saturday, June 15, 2024.